Frequently Asked Questions

There are many others that have been doing this much longer than I have but here are some questions I get asked often and my experiences thus far. If you have any questions that you don’t see below, please reach out at jeff.b.hester@gmail.com.

-

Rarely. I have a pool of a few assistants that I use regularly, and my life is too chaotic to do justice to anyone interning with me! But for assistants, you need to be a water person, have at least 100 hours on a rebreather, and it’s a bonus if you can shoot some banger BTS. You also need to have a good attitude, be a quick learner, be incredibly detail-oriented, and be a generally enjoyable person to be around. The ability to do the job obviously comes first but life is too short to spend most of my year with annoying people.

-

Every person you ask will have a different answer to this one. There does seem to be a larger proportion of people that came from the sciences and moved into filmmaking, but by no means is that a requirement. Personally, I went to college for a degree in Biology and assumed I would take the route of academia which was, to finish undergrad, apply for Ph.D. programs, obtain a Ph.D., then move on to be a Post Doc or professor/researcher. Immediately after college, I was on that path and working as a scientist for NOAA in the marine mammal genetics lab. After a year there, I was awarded an incredibly life-changing opportunity and was named the 2013 North American Rolex Scholar for the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society. I highly recommend that any individuals interested in a career in the ocean look into this, although it is only open to those under the age of 26 and without a graduate degree. I spent a year traveling around the world, getting loads of experience with photography/filmmaking and technical diving, and came out of the year with a newfound career path of underwater image making.

From there, the industry is mostly set up like an apprenticeship. I was able to go on shoots and learn from some amazing camera operators as their underwater assistant. Initially, it worked well for me to have a lot of drone experience, because I would get hired to shoot drone but then I could also assist underwater, which is where I really wanted to be. I’ve also had a few key mentors along the way that I wouldn’t have been able to make it without, including Hugh Pearson, Doug Anderson, and Roger Horrocks.

I’ve found for most things in life, if you’re really invested in it, just keep doing it and most of the time, it works out. Keep forming new relationships with others in the industry, keep improving your skill set, don’t burn bridges, be a decent human being, and recognize opportunity when it comes knocking.

-

As much as you can possibly get. Everyone’s different, some people take to it naturally while others really have to work at it. Try and get a variety of experiences!

-

It really depends, but most likely, no. I never moved over to Bristol. For those seeking the Director of Photography route, especially underwater, I’d recommend moving somewhere where you can practice diving and using a camera as much as possible as that will serve you better in the long run. Popping over for meetings in Bristol is easy and useful to get your name out there but having the ocean in my backyard has been the greatest asset for my career. I get to test new kit and hone my skills whenever I want, I can go do a 2-hour dive in the morning and still have a regular day. I also get to spend a lot of time observing animal behavior, thinking about unique sequences, and shooting stock footage that I can sell for another stream of income. If you want to go the producer route, you can still make it in wildlife without moving to Bristol but heading over there will probably accelerate your trajectory as it’s a bit harder when you’re just starting out to be remote. Plus, if you have interesting stories, most companies already have teams of producers and researchers, making it tricky to find a role for you if you pitch those stories and they pick them up.

-

Spend a lot of time in the water, be constantly curious and accumulate different skills that interest you, be hyper-critical of your work, and study the programs and sequences that are already out there. And then practice, practice, practice, get out there and shoot, try putting together a sequence, and then once you have a sequence you’re proud of, send it off to some producers for critique (or me, happy to send my thoughts along as well). Don’t take criticism personally, it’s an opportunity to learn and grow.

-

I used to but it became too difficult to manage. If there’s something you’re interested in, send me a message, but it’s best if it’s something where you know exactly what you want (i.e. “I want X kelp photo in 24” x 36” on aluminum with a black frame”).

-

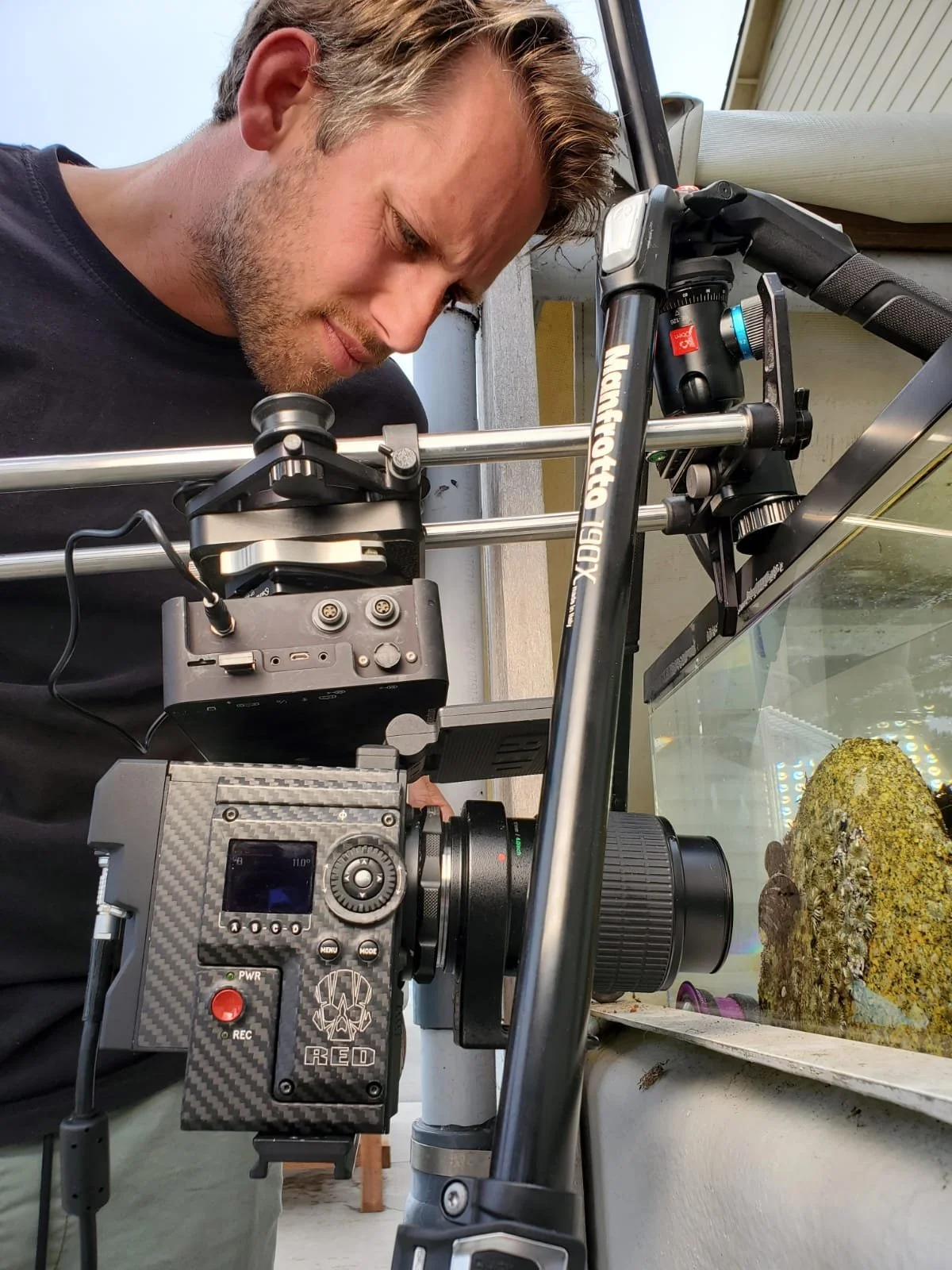

I personally own a variety of my own kit but there’s not a one size fits all answer. When approaching a shoot, I think about what we’re trying to achieve, and build the kit list off that to suit the story we’re trying to tell. But in general, we’re using some type of RED camera in a Gates or Nauticam underwater system. At the end of the day, the kit is just a tool we use to tell a story, so don’t get too caught up in K’s or frame rates if that piece of equipment isn’t going to drive the sequence forward. And then for diving, I’m usually either on my rEvo micro rebreather, open circuit with a steel 100, or open circuit with a small pony bottle for really dynamic work.

-

If you want to work underwater, you need to get to a point where you’re completely comfortable and self-sufficient in the ocean. Dive as much as possible in as many environments and conditions as possible. The ocean is not the place to mess around with being unprepared or saying you can do more than you can, it’s an unforgiving place and can cost you your life. Diving needs to become second nature and being competent on a rebreather is almost a must these days. The rEvo micro is currently the most popular one amongst the wildlife folks and is also what I use. They’re super compact, easy to travel with, and have some nice redundancies.

After diving, it’s learning the operation of different camera systems. Optics work differently underwater than they do above water so you’ll need to familiarize yourself with what setups to use in what situations. If you’re starting out as an AC, learning the kit inside and out so you can assemble it and troubleshoot. Reach out to operators in your area and see if they’ll spend some time running you through different systems, most people in the industry are very kind and will gladly oblige (especially if you bring along some coffee to show your appreciation for their time). The more tools you can begin to put in your tool belt, the greater the breadth of work you can potentially secure. Not to say you should go out and get every certification under the sun, but if certain things interest you and there’s a use for that skill on a shoot, go for it! I think the best cinematographers are the ones that are continuously learning, always trying to figure out how they can improve their craft.

-

As with every yes/no answer, it depends! I didn’t, and I know a lot of people in the film industry that didn’t, so it’s by no means a requirement. There’s so much information everywhere now that you can learn the technical side of cameras as well as storytelling by going to workshops, reading books, or researching online. The main benefits I potentially see in attending film school would be networking, being forced to make films (although if you must be forced, it’s probably not for you), and getting your hands on equipment that you might not be able to otherwise. But again, I didn’t go, so I’m probably not the right person to ask this question.

-

It can really vary depending on your position. I like to treat my freelance career like a business. I enjoy finding alternative income streams that can complement what I do. At the end of the day, you must remember that you get paid a DAY rate, meaning if you want to make more money, you have to spend more days in the field, more time away from friends and family, more missed birthdays, weddings, anniversaries etc. So, I’ve found things like renting my own kit to productions and shooting stock footage that I can continuously sell as good ways to supplement my day rate as a DP. If you’d like to know more about day rates and rental rates, drop me a message and I’ll send over my rate sheet.

-

There are so many good cameras out there now that unless you’re getting extremely specialized, just buy the one that fits your budget, it will most likely do what you need it to do. And again, at the end of the day, it’s just a tool we use to tell stories.